In part one of this series, we talked about estrogen formulations in contraceptives. In hormonal contraception, while estrogen supports cycle control and bleeding patterns, progestins are primarily responsible for suppressing ovulation, thickening cervical mucus, and creating an endometrial environment that prevents implantation. We will dive into this topic more in part two.

Progestins in Contraception

You might reasonably ask: if progesterone is the body’s natural hormone, why don’t we just use progesterone for contraception?

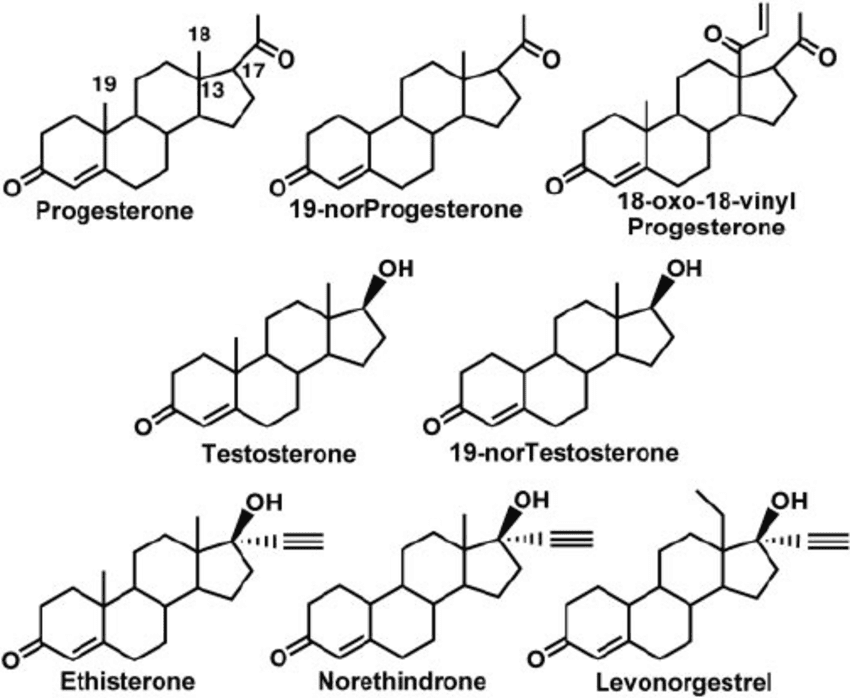

The short answer is pharmacology. Progesterone is rapidly broken down by the liver, has low oral bioavailability, and a short half-life, making it difficult to achieve consistent ovulation suppression with once-daily dosing. To solve this, researchers developed synthetic progesterone analogues (progestins) designed to be more potent, longer-lasting, and reliable when taken orally or delivered locally.

Testosterone, by contrast, is a structurally robust steroid hormone with good oral stability. Chemists modified the testosterone backbone to create molecules that could strongly activate the progesterone receptor while remaining orally effective. The trade-off is that these molecules retain some ability to interact with androgen receptors—what we refer to clinically as androgenicity. Androgenicity is not a binary property. It exists on a spectrum and reflects how much a progestin can “behave like” an androgen at certain tissues.

Over time, different progestins were developed with slightly different receptor profiles. Some retain structural similarity to testosterone, others are modified to behave more like progesterone. These differences explain much of the variation in androgenic effects, potential side effects and tolerability between hormonal contraceptive methods.

A brief note on “generations”

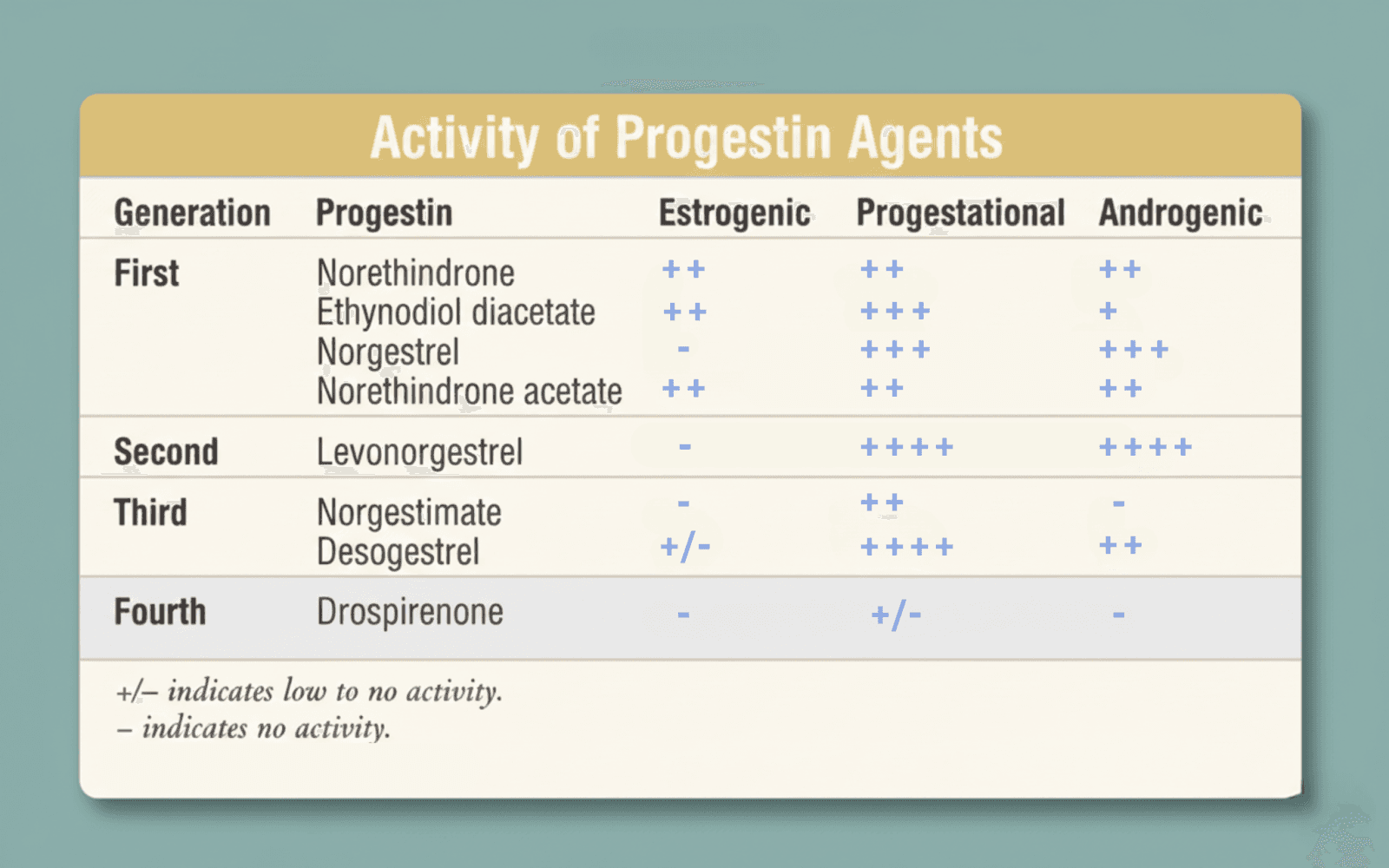

Progestins are often grouped into “generations,” which broadly reflects when they were developed and their structural lineage. While this framework is used less rigidly today, it remains a helpful way to understand formulation differences. Progestins can be classified into four distinct generations.

Note: The generational classification system is being used less frequently in current clinical practice. As such, any references to a 5th generation progestin are unclassified and recognized as ‘later generation’ progestins with higher specificity for the progesterone receptor, currently referred to as “4th generation” progestins.

First generation: effective but moderate androgenic effects and a short half-life

First-generation progestins such as norethindrone, norethynodrel, and ethynodiol diacetate were testosterone-derived and highly effective at suppressing ovulation. Because of their structure, they also had measurable androgenic activity. In some individuals, this can present as acne, oily skin, or increased hair growth. A key pharmacologic limitation of these early progestins was their short half-life (9h). This required precise daily dosing to maintain consistent ovulation suppression and endometrial effects, and contributed to greater sensitivity to missed or delayed pills. These characteristics shaped efforts to create progestins with longer half-lives and reduced androgenic effects. They, however, laid the foundation for oral contraception and clearly demonstrated that ovulation suppression was achievable with oral hormones (1).

Second generation: strong ovulation suppression

Second-generation progestins, most notably levonorgestrel and norgestrel, were designed to enhance progestational potency. They remain among the most effective agents for ovulation suppression and are widely used across pills, implants, and intrauterine devices. Like first-generation agents, they are testosterone-derived and can exhibit androgenic effects, although individual responses vary considerably (2-4)

In combined pills, estrogen is often relied upon to counterbalance androgenic activity by increasing sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), thereby reducing circulating free testosterone. However, this effect is not uniform. Differences in metabolism and receptor sensitivity might explain why some people tolerate these formulations very well while others experience androgen-related side effects.

Third generation: reduced androgenicity, with important distinctions

Third-generation progestins were developed to reduce androgenic side effects while preserving reliable ovulation suppression. This group includes desogestrel, gestodene (primarily used in Europe), and norgestimate, along with their active metabolites.

Desogestrel and norgestimate are pro-drugs. Desogestrel is converted to etonogestrel, its active metabolite, while norgestimate is converted primarily to norelgestromin, with only partial conversion (approximately 20%) to levonorgestrel. These differences help explain why third-generation progestins can behave quite differently in clinical practice, despite being grouped together.

In general, many users experience improved skin and hair tolerability with third-generation progestins compared to earlier testosterone-derived agents. Norgestimate, in particular, tends to have anti-androgenic or neutral androgenic effects, which is why it is commonly used in formulations aimed at acne or androgen-driven symptoms.

When it comes to venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk, nuance matters. Studies have suggested that desogestrel- and gestodene-containing combined oral contraceptives may be associated with a modestly higher relative VTE risk compared with levonorgestrel-containing pills (5). However, norgestimate does not appear to share this increased risk and is generally grouped with levonorgestrel in terms of VTE profile, despite its third-generation classification (6).

Fourth generation: progesterone-like signalling

Later progestins such as drospirenone, dienogest, and nomegestrol acetate represent a shift away from testosterone-derived structures altogether. These molecules are designed to more closely resemble endogenous progesterone and tend to have anti-androgenic properties and less impact on fluid retention. Drospirenone, for example, is structurally related to spironolactone, which helps explain its mild diuretic and anti-androgenic effects. From a formulation perspective, this reflects a broader move toward greater receptor selectivity, rather than simply increasing potency (7).

Distinct progestin affinity for estrogen, androgen, and progesterone receptors (8).

Conclusion

The hormones used in contraception were designed with a very specific purpose: to reliably suppress ovulation, control the menstrual cycle, and work predictably across populations. To achieve that, they needed to be potent, stable, and orally effective - which is why synthetic estrogens and progestins exist in the first place.

Rather than thinking of progestins as better or worse, it’s more accurate to think of them as different tools, each optimized for slightly different priorities - strong ovulation suppression, lower androgenicity, improved tolerability, or additional non-contraceptive benefits.

Side effects are real, and individual tolerance varies widely. We think it’s due to genetic differences, as well as differences in metabolism, receptor sensitivity and one’s baseline. Individual responses vary widely, which is why formulation details matter and why contraceptive prescribing is never one-size-fits-all.

In Part 3, we’ll shift gears and look at hormone formulations used in menopause hormone therapy, where the goal is not ovulation suppression. We’ll explore how and why those formulations differ.

Authors: Dr Paulina Cecula, Namrata Ashok. Reviewed and edited by: Dr Aaron Lazorwitz, Elena Rueda

References:

1. Graham S, Archer DF, Simon JA, Ohleth KM, Bernick B. Review of menopausal hormone therapy with estradiol and progesterone versus other estrogens and progestins. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2022 Sep 8;38(11):891–910.

2. Weill A, Dalichampt M, Raguideau F, Ricordeau P, Blotière PO, Rudant J, et al. Low dose oestrogen combined oral contraception and risk of pulmonary embolism, stroke, and myocardial infarction in five million French women: cohort study. BMJ [Internet]. 2016 May 10;353:i2002. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/353/bmj.i2002

3. Darney PD. The androgenicity of progestins. The American Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 1995 Jan 16 [cited 2022 Dec 1];98(1, Supplement 1):S104–10. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002934399800679?via%3Dihub

4. Drug Safety . Yasmin: risk of venous thromboembolism higher than levonorgestrel-containing pills [Internet]. GOV.UK. 2011. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/yasmin-risk-of-venous-thromboembolism-higher-than-levonorgestrel-containing-pills

5. de Bastos M, Stegeman BH, Rosendaal FR, Van Hylckama Vlieg A, Helmerhorst FM, Stijnen T, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thrombosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2014 Mar 3;(3). Available from: https://www.cochrane.org/CD010813/FERTILREG_contraceptive-pills-and-venous-thrombosis

6. Wang L, Luo X, Ren M, Wang Y. Hormone therapy with different administration routes for patients with perimenopausal syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2025 Feb 13;41(1):2462067–7.

7. Mehta J, Kling JM, Manson JE. Risks, Benefits, and Treatment Modalities of Menopausal Hormone Therapy: Current Concepts. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2021 Mar 26;12(564781).

8. Rice C. Selecting and Monitoring Hormonal Contraceptives: An Overview of Available Products [Internet]. www.uspharmacist.com. 2006. Available from: https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/selecting-and-monitoring-hormonal-contraceptives-an-overview-of-available-products